بأقلامهم (حول منجزه)

صالح الرزوق وسكوت ماينار: ملاحظات حول الترجمة الإنكليزية لكتاب "يتهادى حلما"

لماجد الغرباوي

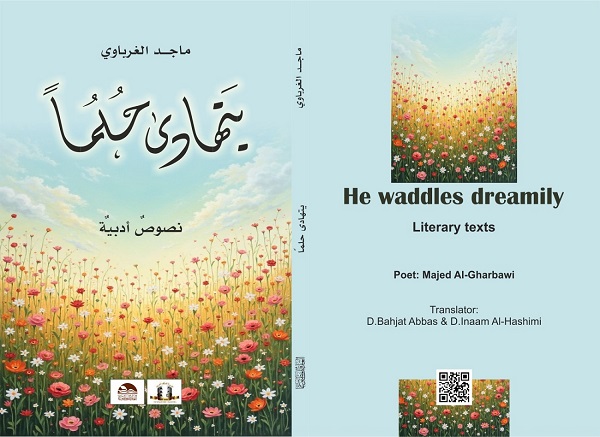

صدر حديثا عن مؤسسة المثقف العربي ودار العارف النسخة الإنكليزية من "يتهادى حلما" لماجد الغرباوي، بترجمة كل من الدكتور بهجت عباس والأستاذة الدكتورة إنعام الهاشمي.

يضع هذا الكتاب الصغير (27ص) أمامنا مجموعتين مختلفتين من النصوص الأدبية. وكما عودنا الغرباوي عبر خمسة عشر مجلدا ناقش فيها مشاكل تجديد وعصرنة العقل العربي، يحرص في هذه الزمرة من النصوص (أشعار وقصة واحدة) مخاطبة مسائل حرجة - وبالأساس الخيال وعلاقته بالواقع. على سبيل المثال في قصيدة "همسات لاهثة" يصور وضعية الإنسان المفرد وهو يتخبط داخل إحراجات واقعه. لكنه في "شظايا" يبحث عن السبل التي يؤثر بها الواقع والمجتمع وسياقه بحياته العقلية والنفسية، وهذا أيضا هو موضوع نصه الأخير وهو قصة "تمرد".

وأحد أهم الجوانب في هذه الكتابات أنها جاءت في سياق مشروع تحديث الأنواع. فقد حاولت أن تلغي الحدود بين أسلوب الحكاية المروية والشعر المكتوب، وأن تفهم المشاعر بواسطة المشاعر، وقد برز هذا التيار في الستينات على يد جمعة اللامي في العراق، وتوفيق يوسف عواد في لبنان (انظر كتابه المبكر والنوعي "عذارى" والذي صدر عام 1944 بعد خمس سنوات من روايته "الرغيف". وهي علامة بارزة في تاريخ الواقعية الجديدة - أو الحرة.

ثانيا سيلاحظ قارئ الغرباوي غياب الشخصيات وسيطرة الأصوات (لا بالمعنى الذي أسس له جبرا ولكن بالمعنى الذي بلوره كل من فرجينيا وولف وفولكنر وعرّبته غادة السمان). فهي غالبا أصوات حزينة ومعزولة، وتعبر موضوعيا عن قنوط الأفراد وهم يكافحون ضد مجموعة من المعوقات والموانع. ويتضح هذا الاتجاه في كتابات ما نسميه جيل الهزيمة، أو باختصار جيل "البيت Beat " الذي أشعلت شرارته حرب عام 1967 - ابتداء من زكريا تامر وحتى إدوار الخراط.

ثالثا يضع الغرباوي قراءه أمام حالة اغتراب قسري عن الواقع الخارجي، ويتلازم ذلك أيضا مع التزام غير اختياري بالظروف والقانون الوضعي الناجم عنها. وعليه تتبنى معظم كتاباته نبرة إما هي مجزأة وغامضة أو هذائية وشيزوفرانية.

وبالطبع إن كل هذه المواصفات والمعايير لم يكن من المقدر متابعتها إلا من خلال عين وأسلوب المترجمين الأفاضل. واتسمت الترجمات بالإيقاع السريع الذي يتلاءم مع المرحلة الحالية والحديثة من حياتنا. فالجمل قصيرة، ومتتالية، ومع قليل من أسماء الوصل وأدوات التعريف والتنكير. وتقدم الصياغة الإنكليزية إلماعات لافتة للانتباه أو الأدق أن نقول "متحورات"، مثل عبارة " in echo flutter kidnaps" عوضا عن الصيغة المتعارف عليها "in echo flutter kidnapping" وهو ما قد يتوقعه المتكلم باللسان الإنكليزي. وبنتيجة هذه اللمسات الخفيفة والرشيقة تتبلور التراكيب اللغوية ويتكون المجاز الشعري الموازي كما نلاحظ في أعمال الشاعر الرمز والاس ستيفنز. ولا شك أن هذه الترجمات تبدو مناسبة للمضمون التجريدي الذي اتبعه كاتب ممزق وحائر بين التزاماته الإنسانية والواقع المفروض عليه بالقوة والعنف والإكراه.

***

صالح الرزوق / أبو ظبي

سكوت ماينار / جامعة أوهايو في لانكستر

........................

Notes on “He Waddles Dreamily” by Majed al-Gharabawi

Saleh Razzouk with Scott Minar

***

The Arab Intellectual Foundation and Dar al-Aref recently published " He Waddles Dreamily" by Majed al-Gharbawi, in translation by Dr. Bahjat Abbas and Dr. Inaam al-Hashimi.

The chapbook presents a collection of two different literary texts. As al-Gharabawi has accustomed us to in more than fifteen volumes in which he discusses renewal and stagnation in the Arab mind, these poems address critical issues - such as the imagination and its relationship to reality. For example, in “Breathless Whispers,” the poet explains the position of human beings inside their realities, while in “Splinters” he explores the ways in which mental or psychological life are affected by reality and social influences or contexts, which constitute the subjects of his last piece, “Rebellion.”

One of the most interesting and notable aspects of these writings is that they come within the context of a genre-modernizing project. They attempt to erase the boundaries between storytelling and poetry, and to interpret emotions through emotions, a movement that emerged in the 1960s with Jumaa al-Lami in Iraq and Tawfiq Yusif Awad in Lebanon.

Secondly, al-Gharabawi’s readers will notice the absence of characters in favor of the prominence of voices. These are often sad and lonely voices. They objectively express the despair of individuals as they struggle against a set of restrictions and constraints. This trend was apparent in the writings of what we call the Generation of Defeat or, in short, the Beat Generation of the 1960s and beyond — from Zakaria Tamer to Edwar al-Kharrat.

Thirdly, al-Gharabawi presents his readers with a detachment from external reality paired with an adherence to circumstances and the canon they produce. Therefore, much of this writing adopts a tone that is either fragmented and vague or delusional and schizophrenic.

All of these features are, of course, seen through the work of al-Gharabawi’s translators. The translations are characterized by a rapid pace appropriate to the modern era. The sentences are short, consecutive, with few articles or relative pronouns. The English phrasing presents interesting flares or adaptations, such as "in echo flutter kidnaps" instead of the more conventional "in echo flutter kidnapping” readers might expect. The result of these gestures is an articulation of language and poetic complexity like the one we might observe in the work of Wallace Stevens. The translations seem well adapted to the figurative language of a writer torn between his obligations and the reality imposed upon him by force, power, and coercion.